DEADLY DOSE

Part 2: As dangerous kratom products go unregulated, lobbyists write the laws

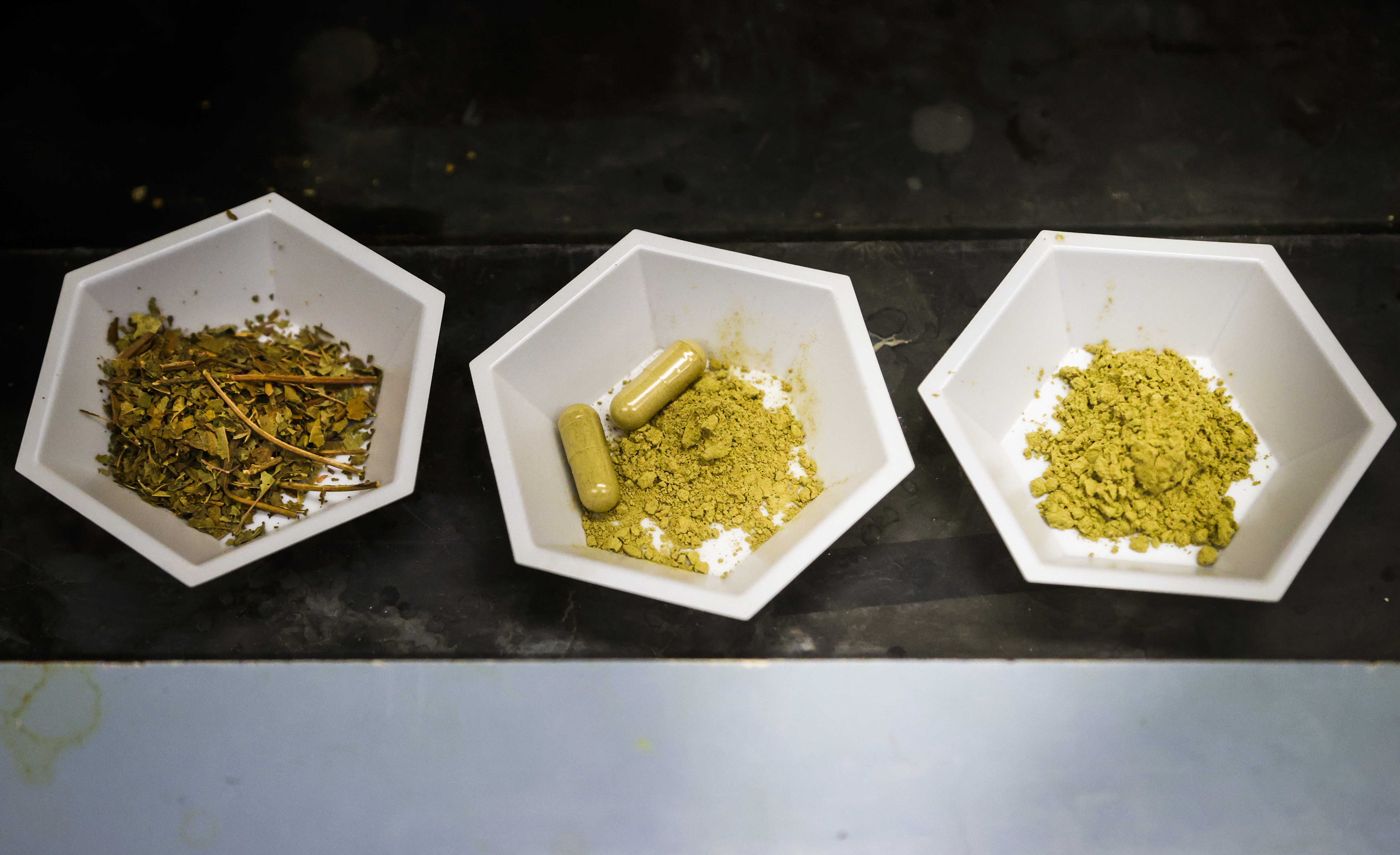

Upstart companies around the country sell crushed kratom leaf, providing no clear dosing instructions or warnings about potential dangers.

They don’t have to.

As medical examiners log an increasing number of overdoses involving kratom across Florida and elsewhere, the industry has largely operated without government constraints or safety measures that could help protect consumers.

Florida lawmakers considered banning kratom three times in the past decade. But industry advocates successfully fought the efforts, ensuring powders, gummies and liquid extracts are readily available at gas stations and smoke shops from Pensacola to Miami. The products vary dramatically in strength — but manufacturers don’t have to disclose or limit their intensity at all.

“It’s totally a wild, wild west market. Buyer beware,” said Christopher McCurdy, a kratom researcher at the University of Florida. “You never know what you’re going to get in this business.”

Florida’s story is emblematic of the nationwide struggle over how to regulate kratom, a plant from Southeast Asia that can act like a stimulant or a sedative, depending on the dosage. Many consumers swear by the substance, taking it to treat a range of ailments from anxiety to chronic pain. But there’s a void of conclusive information on how to safely use it.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has supported a kratom ban, but the agency’s efforts have collapsed amid opposition from lobbyists and consumers. Regulators also haven’t been able to agree on the threat posed by the substance.

With federal officials doing little to oversee the herb, the American Kratom Association has emerged as the predominant force in setting regulations that govern its own $1.5 billion industry, the Tampa Bay Times has found.

The Times analyzed legislation championed by the association in each of the 34 states where bills were introduced in the past five years. Many contain nearly the same language crafted by industry lobbyists. In Massachusetts, for instance, seven out of every 10 words in its 586-word kratom bill were identical to a version in Kansas.

The association spent more than $4.4 million to move these bills through statehouses from Wisconsin to Texas and from Arizona to New York — as well as through Congress — lobbying disclosure records show.

The primary focus of the 34 bills — all touted by the association as consumer protection acts — is to preserve the right to buy and sell kratom rather than institute key guardrails for businesses and those who take it, the Times analysis found.

Most of the bills don’t require companies to list on product labels the quantity of kratom’s main chemical compound that affects strength. None of the bills limit the amount of the compound in products, leaving potent options widely available. Only one version of the bill would have required that companies warn consumers about the risk of combining kratom with other substances.

The state legislation makes a broad range of kratom products legal for those over 21. It allows companies to sell kratom without first having to conduct studies to prove that their products are safe.

Across the country, lawmakers have been swayed by industry talking points about the safety of kratom. Several have voted on bills after admitting they’ve never heard of the substance. In some cases where state officials have proposed tighter regulations, including inspections of kratom retailers, the association’s lobbyists have successfully fought back.

Meanwhile, the association has promoted and collected donations from big brands that have sold products linked to overdose deaths in Florida. It has defended supercharged kratom extracts that scientists worry are harmful.

“What’s found in the plant could be dangerous at very high levels,” said Albert Garcia-Romeu, a kratom researcher at Johns Hopkins University. “That’s something that’s fairly easy to do if you’re creating these extracts.”

The association has combated claims that kratom can kill, blaming overdose findings on a disinformation campaign by the FDA that has influenced medical examiners. (The kratom association also accused the Times of engaging in a conspiracy with trial lawyers to publish this investigation.)

The group runs a program purporting to ensure companies make products safely that two former auditors say is little more than a marketing ploy and does little to protect consumers.

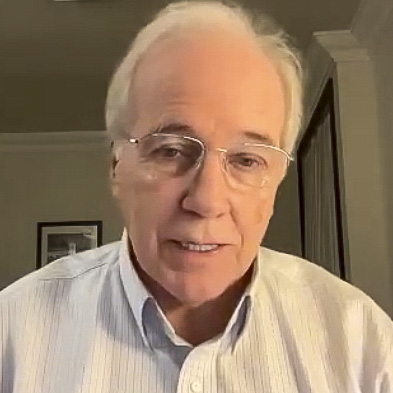

C. McClain “Mac” Haddow, a former Reagan administration official who serves as the American Kratom Association’s lead lobbyist, said the association’s bills would improve safety. The bills outlaw kratom that has been synthetically enhanced or spiked with drugs. Most also say kratom should come packaged with a label that tells consumers how to responsibly use it.

The group’s manufacturing guidelines help kratom companies at a time when the FDA is abdicating its duty to regulate the industry, Haddow said.

Highly concentrated products, he added, could be banned if they were proven to cause deaths. But Haddow blamed dangers associated with kratom on irresponsible consumer behavior.

“Can we regulate stupid?” Haddow said. “I can’t do that — no one can.”

The first part of the Times’ investigation showed that over 580 people in Florida have died from kratom-related overdoses during the past decade. More than 90% of the deaths occurred since 2017. The majority of the cases involved a lethal mix of multiple substances, but medical examiners found kratom alone responsible for dozens of fatal overdoses.

The Times commissioned testing of kratom products and identified pills and liquids that were power-packed, including tablets so strong a scientist compared them to “legal morphine.” They didn’t come with a label detailing their potency.

The FDA has deemed kratom to be dangerous. Not a conventional food nor an approved drug, the herb doesn’t neatly fit into any regulatory box at the federal level.

Companies have repeatedly tried to get the FDA to sign off on products as dietary supplements under an industry-friendly framework pushed by lobbyists, including Haddow, decades ago. That hasn’t convinced the FDA, so Haddow has taken his case to Congress and state lawmakers.

READ PART 1 OF THE INVESTIGATION

Hundreds died using kratom in Florida. It was touted as safe.

The FDA declined repeated interview requests to speak with Times reporters.

In a statement, the agency said it has taken action when unlawful kratom products enter the market — issuing warning letters or seizing material from manufacturers. The agency also works with customs officials to stop kratom from entering the country at ports, according to Lauren-Jei McCarthy, an FDA spokesperson.

“The FDA takes its public health mandate seriously and our focus is on the health and safety of the public,” McCarthy wrote in an email. “The FDA will continue to work with our federal partners to warn the public about risks associated with use of kratom and warn the public against the use of kratom for medical treatment.”

Kratom is listed as illegal in six states and several municipalities and counties, including Sarasota County. Lawmakers in Mississippi, Georgia and West Virginia proposed bans earlier this year.

Many scientists who study kratom don’t think prohibition is the answer. They see the herb as a safer alternative to dangerous drugs driving the opioid epidemic. Some also want to use the plant to develop a gentler treatment for painkiller addiction.

Researchers acknowledge that the kratom industry is challenging to govern, however, because so much remains unknown. No serving size has proven beneficial — nor is there an agreed-upon toxic dose.

Consumers are left largely on their own to evaluate the safety of kratom products and the legitimacy of their claims.

The results can be tragic.

Weston Walker, a St. Petersburg attorney, used kratom with friends from his gym, often going to kava bars after a workout. But eventually the health-conscious world traveler, who once hiked in the Himalayas, started taking concentrated extracts.

During a trip to a central Florida golf resort in August 2021, Walker told a friend he felt overheated, then collapsed in their room. A medical examiner determined he died after taking a lethal amount of kratom.

His sister and a friend said they later found empty extract bottles throughout his Shore Acres home. In his closet, gym bag, everywhere.

“It’s still so unbelievable,” his sister, Whitney Briggs, said. “You just never imagine your 37-year-old, healthy-as-a-horse brother is going to pass away.”

Despite increasing concerns and scientific uncertainties, the American Kratom Association for years has insisted on the herb’s safety.

"Even extremely high doses — doses that, when adjusted for humans, would be difficult to consume — do not cause death or significant toxic effects," Haddow said in a 2018 news release, citing studies conducted on animals.

In recent months, after two separate courts found kratom businesses liable in wrongful death lawsuits, Haddow has sent mixed messages.

Over the summer, he circulated a “consumer advisory” to reporters around the country. It contained a caveat.

“There is no known level of kratom use that would cause any fatality,” Haddow wrote.

But he added: “unless it is irresponsibly consumed.”

“Tying our hands”

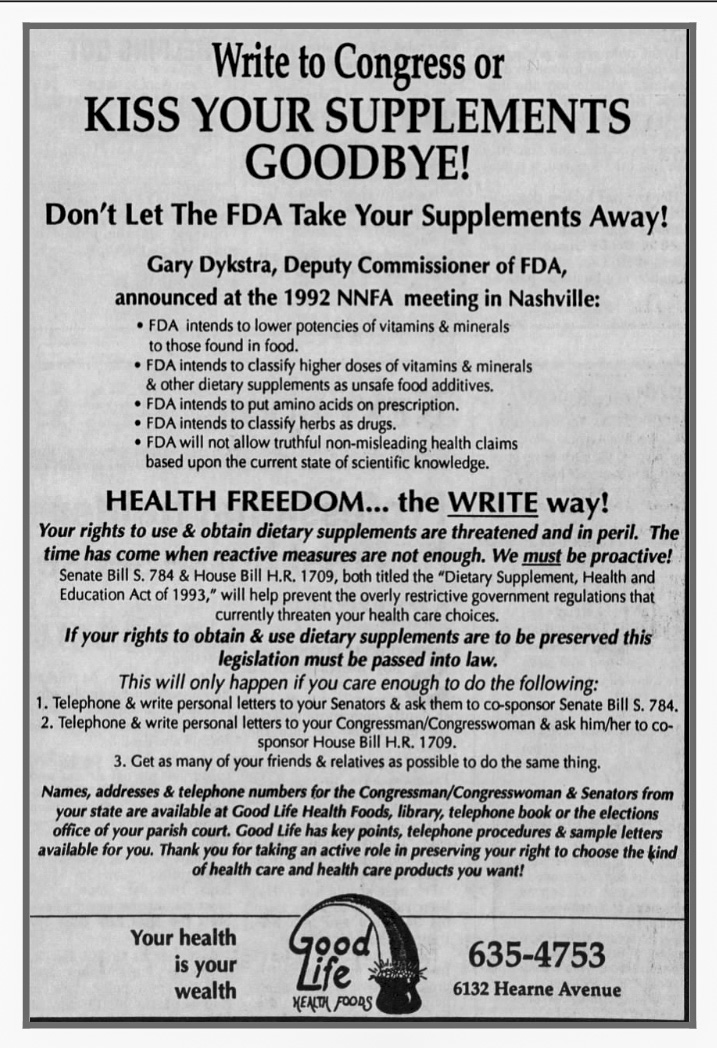

In the 1990s, the FDA faced a similar dilemma to the one it’s confronting now with kratom. That time, the agency was outmaneuvered by the dietary supplement industry. Just like today, Haddow was in the middle of the lobbying effort.

For decades, federal officials had few tools to govern strong vitamins, amino acids and other products marketed to have wellness benefits.

The FDA tried to rein in the industry by restricting the types of health claims businesses could make about supplements. The agency encouraged companies to either prove the benefits of their products scientifically or remove such claims from their labels.

Haddow played a role in the creation of a law to circumvent the supplement industry’s trouble with the FDA by advising the bill’s sponsor, Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch, on its framing. Decades earlier, Haddow had managed Hatch’s first successful Senate campaign.

While the bill’s specifics were hammered out, the industry organized a nationwide day of protest. At one health store, staff placed vitamins and other wellness products in a coffin to hold a mock funeral. At others, shoppers could only buy supplements if they agreed to write to Congress. Lawmakers reportedly got more letters about dietary supplements than they did about the Vietnam War.

In 1994, Congress unanimously passed the Hatch-sponsored Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act. The law forced the FDA to presume that dietary supplements already on the market were safe, meaning companies didn’t need to first conduct studies for proof. Only products with novel ingredients had to demonstrate they wouldn’t pose too much risk to consumers. The legislation further meant that the FDA would need to go to court to prove supplements were unsafe before removing them from stores.

The supplement industry has thrived since. In 1994, it sported 4,000 products and made at least $4 billion in annual sales. Today, market research firms estimate that sales are at least 10 times that.

Gary Dykstra, who led a dietary supplement task force for the FDA in the ’90s, said that because of the law, the FDA could do little more than ask companies to put warning labels on dangerous products.

“They did a pretty good job of tying our hands,” Dykstra said. “Obviously products came along that did cause problems, and it was difficult to take action against them.”

Workout supplements containing ephedra killed dozens before the FDA banned them in 2004. Scientists have attributed an estimated 23,000 emergency room visits per year to adverse reactions involving dietary supplements, according to a 2015 study published by The New England Journal of Medicine.

People in the supplement industry defend the law, arguing that the FDA has the tools it needs to protect consumers from dangerous products.

Some even point to kratom as an example. The 1994 legislation that helped the supplement industry ultimately created hurdles for kratom manufacturers, according to Scott Bass, an industry attorney who helped craft the legislation.

Because there was no evidence the herb was on the market at the time of the law’s passage, kratom makers have had to convince the FDA their products are safe before they can legally sell them as supplements. At least five have tried.

After each review, the FDA has ruled that the products would be too dangerous to be regulated under the supplement industry’s limited oversight system.

But Haddow and the American Kratom Association were determined to look for other options. They’ve gone to Congress, in a move reminiscent of the ’90s supplement industry.

This fall, a bipartisan group of congressional lawmakers filed a bill, pushed by the association, that would exempt companies from having to prove their products are safe — bypassing the FDA entirely.

A game of whack-a-mole

Beyond regulating kratom as a supplement, the FDA has at least three other routes it could take.

It could support a ban. It could aggressively regulate kratom under existing food guidelines. Or it could leave kratom in limbo, neither illegal nor sanctioned.

After years of pushing for a ban, the agency has opted to leave kratom in limbo.

The lack of federal standards coupled with the agency’s failure to supervise the industry’s supply chain has come with consequences.

“Keeping it basically unregulated is doing harm, and by banning it you do harm, so the way to kind of manage this would be to regulate it,” said Garcia-Romeu, the Johns Hopkins researcher. “FDA could find a way to do that, I think, but for whatever reason, they’re just dragging their feet.”

When asked why the FDA has chosen not to regulate kratom under existing food laws, an agency spokesperson did not respond.

The FDA first recorded a person dying in the U.S. after ingesting kratom in 2011. By 2016, the agency supported the Drug Enforcement Administration’s push to add two key kratom ingredients to the list of Schedule 1 substances, like heroin or ecstasy. The effort was beaten back by the American Kratom Association and other advocates.

Two years later, when the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services weighed whether to greenlight a ban for a second time, top officials couldn’t agree on how to proceed. The FDA put out a news release comparing kratom to opioids. Some in the Trump administration found they’d overstated the risks.

Brett Giroir, a top Trump health official, wouldn’t sign off on the ban.

As officials disagreed internally about kratom, they struggled to communicate the danger it poses to the public.

In 2018, the FDA released data from its Adverse Event Reporting System and said kratom was associated with 44 documented deaths.

But at the time, the characterization was controversial. For example, one of the alleged kratom deaths reported by the FDA was a suicide by hanging in 2015 involving a 19-year-old man.

The kratom association went on the offensive, and some researchers also said the FDA lost credibility.

The agency has kept kratom at arm’s length ever since.

At various points, regulators have tried to keep dangerous products out of consumers’ hands, playing a game of whack-a-mole with limited success.

The vast majority of kratom sold in the U.S. comes from Indonesia. The FDA can block products it believes are harmful by issuing what’s known as an import alert.

The agency has published a sweeping alert for kratom, warning that shipments of the herb found by federal agents could be turned away. Despite recent lobbying efforts by the kratom association and the Indonesian government, the alert is still in place. Officials have refused at least 1,150 kratom shipments since 2015, agency data shows.

Many other shipments have gotten through. In numerous cases, companies simply lied about the cargo. But in at least 1,100 instances, importers said they were bringing kratom into the U.S. and were allowed to do so anyway, according to customs data analyzed by the Times. In more than 210 of those cases, companies told the government the kratom they were importing was “not for human consumption.”

Once kratom passes customs, it’s legal to sell and consume in most places.

But the lack of federal rules has left officials unable to effectively respond to hazards.

When a salmonella outbreak infected more than 75 kratom consumers six years ago, the FDA issued an unprecedented mandatory recall of 26 different products handled by Nevada-based Triangle Pharmanaturals. (Numerous other kratom products were voluntarily recalled.)

When officials tried to find the origin of the outbreak, they were stymied by a lack of documentation about how products were manufactured, packaged and distributed, FDA researchers acknowledged in a 2022 paper. The agency struggled to figure out where the tainted kratom came from, delaying its response.

Such challenges are unusual during foodborne illness investigations.

“Under normal circumstances, there are mutual expectations between regulators and regulated entities,” the researchers wrote. “When the expectations and understanding of jurisdiction are absent, inspection and document collection can be delayed or inhibited.”

Federal regulations also generally require dietary supplements and traditional foods to come labeled with specific information, such as a serving size and a list of ingredients.

But kratom products often don’t come with the labeling consumers expect of conventional food.

Of the 20 kratom products the Times bought from online vendors and stores around Tampa Bay, more than half had no dosing instructions or potency details on their labels. A quarter had no ingredients listed.

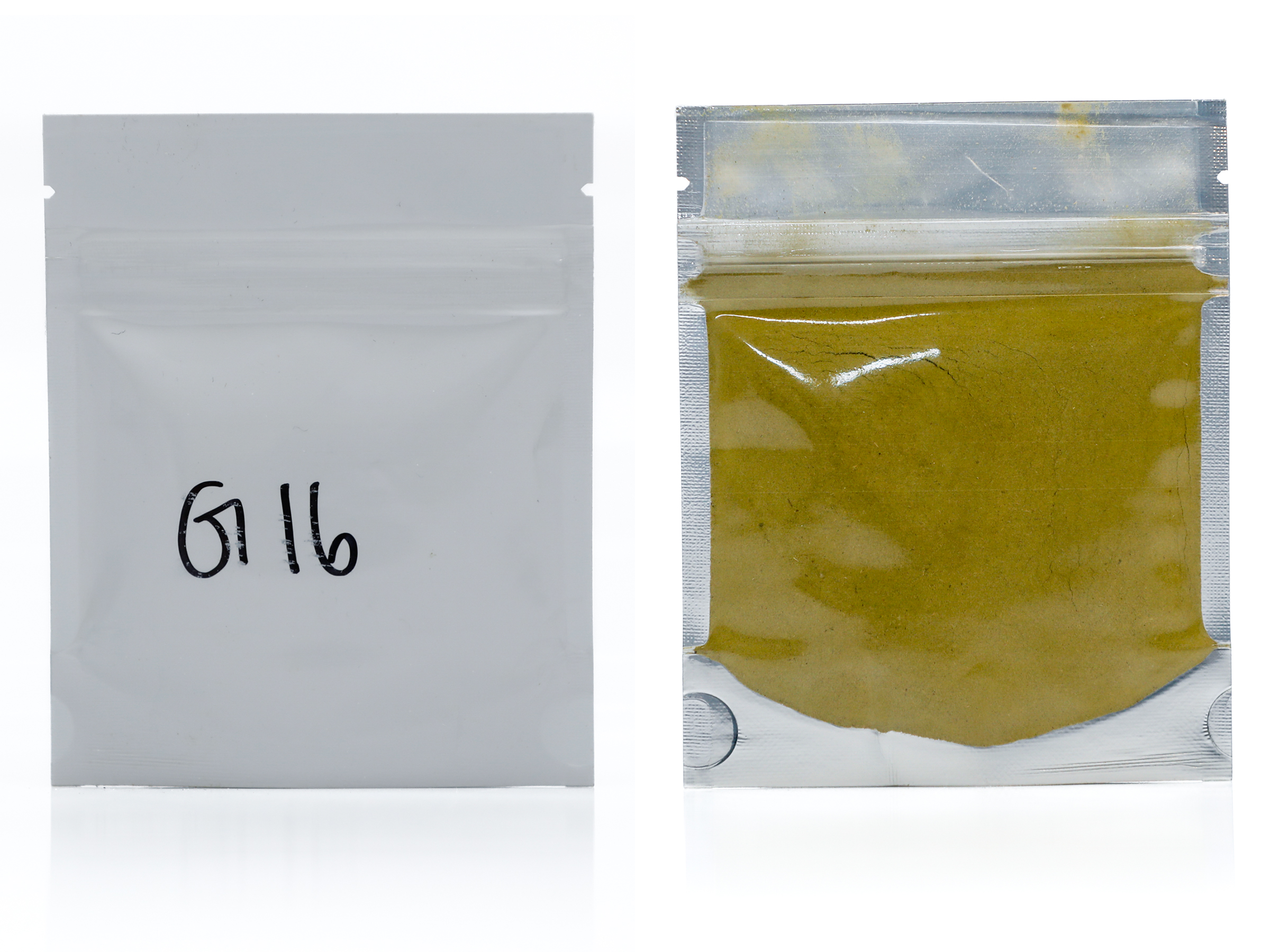

A Times reporter ordered one product from Idaho-based vendor The Kratom Distro. But when the package arrived, the Times found that the brand had sent two bags of kratom powder labeled “old batch” and “new batch” without further explanation.

The Kratom Distro also included two complimentary products. One came in a plastic pouch with nothing written on it except what appeared to be “G16.” (A representative for the brand hung up on a reporter, then did not respond to follow-up requests for comment.)

Minimal labeling wasn’t the only problem the Times found.

Kratom companies aren’t allowed to make medical claims about the herb on labels or in advertising because the substance is not an approved drug. Companies must submit extensive scientific proof to the FDA demonstrating their products’ effects before they can advertise any ability to treat conditions.

Yet kratom vendors routinely boast about the herb’s therapeutic benefits.

A shop in St. Petersburg, Botava.life, handed a reporter a flyer that showed which “strains” of kratom were best for certain ailments, purporting to treat everything from anxiety to opioid withdrawal. Brent Bruns II, the shop’s owner, said he has since removed the language.

“We shouldn’t be making any claims,” Bruns told the Times.

One product called KTAB by Phoria that the Times analyzed advertised “pain relief + mood enhancement” on its packaging. A reporter bought the product from the Colorado-based company. The container of five kratom tablets cost $29.95 online.

The Times’ testing, performed by University of Florida researchers, found that each tablet contained nearly 60 milligrams of mitragynine, kratom’s main ingredient. That’s 14 times what’s in a Whole Herbs Red Vein Bali kratom capsule, a well-known product linked to at least one overdose death in Florida. (Phoria did not respond to requests for comment.)

The FDA has sent letters to 16 kratom companies in the last half-decade warning them against making illegal medical claims.

But the porous system has largely left the industry to self-regulate.

Enter the American Kratom Association.

A lobbying group

Before Haddow was hired to be the American Kratom Association’s lobbyist in 2016, kratom was a largely unknown herb, and the association was an obscure group hellbent on saving it from being outlawed.

The organization has since become the most influential kratom lobbying and advocacy group in the world — aligning itself with some of the industry’s largest players.

It was founded in 2014 by Susan Ash, an environmentalist who turned to kratom to help treat her symptoms of Lyme disease. In the early years, Ash fought proposed kratom bans in several states. She scored early victories, including in Florida.

The organization was still in its infancy when it was confronted with a pivotal moment: the DEA’s attempt to add kratom to the list of federally banned drugs.

“The fight in 2016 really altered the way we had to do business,” said Robin Graham, who served on the group’s board from 2015 to 2019. “Originally, we were simply an advocacy group. Then we became a lobbying and advocacy group.”

No such drug ban had ever been reversed. Ash hired Haddow, a lobbyist with a rare blend of expertise on kratom and the dietary supplement industry.

The kratom association encouraged hundreds of dedicated consumers to protest the DEA’s proposal in Washington, D.C. Kratom companies paid for some of the travel, two former volunteers with the organization said.

Haddow leveraged his connections in Congress, and 51 members of the House signed a letter objecting to the DEA’s decision. Haddow’s ally Hatch, who was serving his seventh Senate term, put together his own letter to the DEA, telling them to stand down.

The feds backed off.

Haddow’s influence over the group steadily grew after Ash resigned in 2017 amid internal allegations of financial improprieties.

Though he’s not listed on tax forms as an employee, Haddow serves as a public face for the American Kratom Association. His title is senior fellow on public policy. The group has an executive director but lists no full-time staffers.

It boasts a significant following among kratom consumers, whom Haddow periodically updates on the organization’s YouTube channel.

The association’s status as a nonprofit means it doesn’t have to disclose its donors. Haddow said the group is primarily funded by 140,000 kratom backers.

“The money that we collect from our advocates, which are people trying to protect the legality of kratom, is the thing that drives our organization,” Haddow said.

The association also lists companies as supporters. As of early December, two dozen brands had earned the group’s designation of silver, gold or platinum level “Kratom Consumer Champions.”

When asked how much money companies give to receive their title, Haddow declined to say. But he added that it’s for vendors who donate to and support the group’s advocacy efforts.

Products from five brands labeled as consumer champions — Choice Botanicals, Golden Monk, O.P.M.S., Remarkable Herbs and Whole Herbs — have been linked to at least seven fatal overdoses across Florida where kratom was the only substance medical examiners blamed, according to a Times analysis.

Businesses also pay the association $5,000 per year to be part of its Good Manufacturing Practice Standards Program, according to its website. Consumers are directed to the brands’ websites by clicking a banner on the association’s site that reads, “Where can I buy safe kratom?”

To participate, businesses agree to have their manufacturing procedures examined and certified by association-approved auditors.

More than 40 brands are designated on the association’s website as qualified vendors.

But two auditors who have worked with the association said the program is so lax that the certification shouldn’t be relied upon by consumers. It’s little more than a rubber stamp that companies get to put on their labels, the auditors said.

One of the auditors, Dana Jolie, has spent his career reviewing the manufacturing processes of food and dietary supplement companies.

Earlier this year, he was asked by Super Speciosa, a kratom vendor, to conduct an audit for the American Kratom Association’s program.

In theory, Jolie was supposed to ensure that the firm abided by a lengthy checklist of manufacturing requirements.

But the company didn’t want him to conduct a full review, he said.

In July, Jolie got an email from Super Speciosa’s quality manager, Joey Levin, asking him to disregard parts of the checklist that dealt directly with how the product was made.

“We’re OK with that,” Levin wrote, “and I think the AKA understands the situation.”

Without the manufacturing part of the audit, Jolie said he would have been left to examine company procedures that have little to do with product quality. He wrote Super Speciosa back, refusing to do it. Then in September, he told the kratom association that he could no longer work on the program.

The association’s executive director, Ryan Burroughs, said in a statement to the Times that companies are not allowed to avoid having their manufacturing practices examined.

“Any audit report submitted by an auditor that did not include a review of the manufacturing process would have been rejected,” he wrote.

SUPPORT GREAT JOURNALISM

Please consider donating to help the Tampa Bay Times bring you more

investigations like this one.

Your support means a lot.

Ken Loricchio, the co-founder of Super Speciosa, wrote in an email to the Times that an audit of the brand would have required a review of how the company ensures its manufacturing vendors are qualified.

But auditing a company’s manufacturing process and looking at an internal evaluation of contract manufacturers is not the same, Jolie said.

As of this month, Super Speciosa was still listed on the association’s website as a qualified vendor.

“The consumer goes out there and thinks they’re being regulated when you get the AKA seal and you say you’re in their audit program,” Jolie said in an interview. “You would assume that, ‘Jeez, these things are all being checked, and it’s pretty strenuous.’ But it isn’t real.”

“Legitimize kratom, nothing more”

Over the past five years, bills pushed by the kratom association have been introduced in 34 states to legalize and regulate the substance. Known as Kratom Consumer Protection Acts, they’ve passed in some form in 11 states, including Florida.

But lawmakers considering the bills rarely demonstrate a firm grasp of what they’re voting on.

In at least three legislative hearings, lawmakers read from cursory internet searches as they questioned the association and one of its experts about kratom.

In Indiana: “I didn’t know anything about this, so I did a little Google search,” one legislator said.

In Wisconsin: “I looked up kratom, as far as being safe or unsafe, and the first thing I find ..." one lawmaker explained.

In Louisiana: “I’m doing a little research,” one legislator said as he read from a website.

In two states, lawmakers said they weren't familiar with kratom, then voted in favor of the association’s bills. One Florida senator called the substance “katron” while presiding over a committee hearing. That senator then voted for the bill.

Haddow has crossed the country arguing that kratom is safe. He tells lawmakers that the substance hasn’t proven deadly. Often, they don’t push back.

In Florida, for example, hundreds of people have died from kratom-related overdoses. Yet just two lawmakers referenced kratom deaths when discussing the association’s legislation during hearings earlier this year. (One voted for it, the other against it.)

Haddow says the legislation has a few central aims. It encourages good manufacturing and labeling practices, keeps kratom from being sold to minors and stops it from being spiked with dangerous substances.

The vast majority of bills propose limits on the amount of one potent kratom alkaloid, 7-hydroxymitragynine, which can be included in products. But the bills are silent on limiting other alkaloids that researchers worry about.

The state-by-state effort, Haddow said, is the way for the kratom community to fight back against the FDA’s anti-kratom stance. In an August video update to the community, he called the proposed bills “the biggest threat to the FDA, and they know it.”

Republicans sponsored the majority of the bills, which typically generate bipartisan support as they gain legislative momentum.

The association’s legislation varies in language and scope from state to state. But much of the wording is consistent: In 15 states, bills exempted kratom retailers from punishments for selling dangerous products if the companies can show they “relied in good faith upon the representations of a manufacturer.”

Twenty-eight of the 34 bills proposed prohibiting kratom vendors from lacing their products with a controlled substance, even though it’s already a crime in every state to sell illicit drugs.

In Texas, Colorado and 20 other states, bills required labels on kratom products directing consumers how to safely use them. Ten bills required companies to register their kratom products with state agencies or to get a license. Five, including in Georgia and Indiana, required companies to list product ingredients.

The bills did little to ensure kratom companies followed federal rules for food or dietary supplement manufacturing. None limited the mitragynine amount in concentrated kratom extracts, which scientists are increasingly concerned about. And none required companies to scientifically justify the safety of their products before they reach stores — as existing federal dietary supplement law requires for products like kratom.

The Times analyzed each of the provisions in the bills, as they were initially introduced, and asked eight researchers to review the findings. They were experts in kratom, pharmacology and toxicology.

Four said the legislation was a positive initial step. All said the bills needed to go further to protect consumers.

Four said the bills should cap product potency by limiting the amount of kratom’s main ingredient mitragynine in liquid shots, powders and capsules. One urged regulating the highly potent extract versions of kratom as drugs — not food. Some brands listed as consumer champions on the American Kratom Association’s website, such as O.P.M.S. and MIT45, sell concentrated liquid extracts that pack more than 75 milligrams of mitragynine into bottles with 1 ounce or less inside.

University of Florida kratom researcher Abhisheak Sharma said he believes consumers should limit daily mitragynine intake to no more than 40 milligrams.

“There is no meaning of any bill until they control the total dose available for human consumption,” Sharma wrote in an email to the Times.

Six experts said the bills should require more robust warning labels, including information about the possibility for dangerous interactions with other substances. Some kratom brands already warn consumers of the risk. But many don’t. The Times found more than 30 cases of people across Florida overdosing from a fatal mix that included kratom and at least one drug used to treat anxiety or depression.

And three researchers said regulators should limit the amount of the alkaloid 7-hydroxymitragynine to a fraction of what the association has proposed — with one saying it should be 96% lower.

“These bills are just designed to legitimize kratom, nothing more,” Alan Kaye, a pharmacology and anesthesiology professor at Louisiana State University in Shreveport, wrote in an email.

Haddow said the association’s legislation is based on scientific studies, not the opinions of individual experts.

“I don’t have any problem with these researchers giving me scientific data that would let us put strengthened provisions in that bill,” Haddow said.

In Florida, state lawmakers ultimately passed a scaled-back version of the association’s bill, defining kratom as a food or dietary supplement, banning sales to those younger than 21 and giving the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services the power to create rules enforcing the law. Gov. Ron DeSantis signed it in June.

Three months later, the agriculture department proposed a rule requiring kratom distributors to get a food permit and pay a $650 annual fee. The companies would be subject to routine inspections from the department, and manufacturers would need to abide by federal rules for making dietary supplements.

In one of his YouTube addresses, Haddow told kratom advocates that the agriculture department had gone too far.

Next year, Haddow says, the association will be heard in Tallahassee once again. Not to speak for the industry, he insists. But for the consumer.

Times staff writers Helen Freund, Langston Taylor and Hannah Critchfield contributed to this report.

Lead photo by Times photo director Martha Asencio-Rhine.

This article was produced as a project with the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2023 National Fellowship.